Commentary

According to an agreement concluded on 7 June 1763 between the Duke of Modena, Francesco III d’Este, and Empress Maria Theresia, the empress’s third surviving son, Archduke Ferdinand, upon reaching his majority, would marry Princess Maria Beatrice d’Este, the Duke’s granddaughter. Ferdinand would also take over the governor-generalship of the Duchy of Milan (Lombardy) from the Duke. At the time of the agreement, Maria Beatrice was just 13, and Ferdinand was only 9: he was born on 2 June 1754, and thus 20 months older than Mozart. Their betrothal was celebrated in 1766 (Sommer-Mathis 1994, 199–200).

The Duke had little interest in governance and had played little role in day-to-day affairs in the duchy, whose de facto ruler was Count Carlo di Firmian (1718–1782), the Habsburg minister plenipotentiary in Milan. As we have shown in our extended commentary “Mozart and Firmian,” the count had quickly taken young Mozart under his wing when Wolfgang and his father Leopold arrived in Milan at the end of January 1770. They dined several times with Firmian at his residence, the Palazzo Melzi; Firmian gave Mozart a copy of the Turin edition of the complete works of Metastasio; he arranged for Mozart to perform for the Duke and Princess on 18 Feb; and he organized a concert on 12 Mar to allow Mozart to demonstrate to the assembled Milanese aristocracy his ability to compose in all the requisite styles of Italian opera seria. Firmian’s underlying plan in all this seems to have been to give the fourteen-year-old Wolfgang the opportunity to prove that he was worthy of a commission to compose an opera for the following carnival season in Milan. Shortly after the concert and just before Wolfgang and Leopold departed the city on 15 Mar, Wolfgang did in fact receive a scrittura, for the opera that became Mitridate. When the Mozarts left Milan, heading south to Bologna, Florence, Rome, and Naples, they were equipped with a large number of letters of introduction, including several from Firmian (see our entry for 4 Apr 1770). The Mozarts returned to Milan in mid-October 1770, where Mitridate had its premiere on 26 Dec and seems to have been a considerable success (see our entries for 1 Jan 1771 and 16 Jan 1771).

The big event of 1771 in Milan was to be the wedding of Princess Beatrice and Archduke Ferdinand, who turned 17 on 1 Jun that year. The wedding was slated to take place in the autumn, accompanied by two weeks of elaborate festivities, including balls, dinners, an outdoor banquet, a horse race, and the premiere of a new opera seria, the commission for which was given to the venerable Johann Adolph Hasse (1699–1783), who was living in Vienna at that time and was a favorite of Maria Theresia. That opera became Il Ruggiero. Ferdinand’s itinerary from Vienna to Milan was elaborately mapped out, with special events and performances at stops along the way. Concurrent festivities celebrating the marriage were planned for Vienna.

At some point early in the planning, Maria Theresia decided also to commission a serenata for the wedding festivities, in addition to the new opera. Just how this commission came to be given to young Mozart has never been clear. Up to now, it has been known only from a teaser in Leopold’s letter to his wife sent from Verona on 18 Mar 1771:

Gestern habe Briefe aus Mayland erhalten, der mir ein Schreiben v Wienn ankündigte, so in Salzb: erhalten werde, und das euch in Verwunderung setzen wird, unserm Sohne aber eine unsterbliche ehre macht.

Der nämliche Brief hat mir eine andre sehr angenehme zeitung mit gebrach.

[Briefe, i:246]

Yesterday I received a letter from Milan that notified me of a communication from Vienna that will be received in Salzburg, and will astonish you, but bring immortal honor to our son.

The same letter brought me another very pleasant piece of news.

The “sehr angenehme zeitung” (“very pleasant piece of news”) was the scrittura for Wolfgang to compose one of the two carnival operas for Milan in the season 1772–73, the opera that became Lucio Silla. The “unsterbliche ehre” (“immortal honor”) was evidently the news that Wolfgang would be commissioned to compose the serenata for the imperial wedding in October 1771. This commission became Ascanio in Alba.

The commissioning letter for the wedding serenata is not known to survive and the archival copy that seems likely to have been retained (by whomever sent it) has not been found. Nissen’s Mozart biography attributes the idea of commissioning Mozart to Maria Theresia herself, and both Nissen and Jahn claim that Firmian, at the empress’s behest, wrote the official commissioning letter to the Mozarts in Salzburg (see Nissen 1828, 250 and Jahn 1856, i:220). Luigi Ferdinando Tagliavini, editor of Ascanio in Alba for the Neue Mozart-Ausgabe in 1956, also accepts this theory (Tagliavini 1956, vii). Joseph Heinz Eibl, on the other hand, in the commentary to the complete edition of the Mozart family letters, ascribes the idea to Firmian, but speculates that Princess Maria Beatrice herself may have promoted the idea (Briefe, v:300). Kathleen Hansell, in her Berkeley dissertation, casts doubt on these notions, suggesting instead that the Milanese public had clamored for Mozart after the success of Mitridate (Hansell 1979, 56). No direct primary evidence is offered for any of these conjectures.

The issue of the commission was resolved by historian Andrea Sommer (later Andrea Sommer-Mathis) in her 1981 dissertation at the University of Vienna, published in shortened form in 1994 as a book. Sommer discovered—and in her dissertation partially transcribed—a draft of a letter dated 9 Feb 1771 from Count Firmian in Milan to Count Johann Wenzel Sporck (1724–1804) in Vienna (Sommer 1981, 489–90, and Sommer-Mathis 1994, 205–6); Spork was Count Giacomo Durazzo’s successor as Hofmusikgraf and General-Spektakel-Direktor, the man ultimately responsible for all official Habsburg court theatrical productions, both at home and abroad. Firmian’s draft, the relevant portion of which is transcribed and translated above, states that the empress has left the choice of poet and composer for the serenata up to Firmian, and in his letter to Sporck, Firmian makes the case for Mozart as the composer. Up to now Sommer-Mathis’s discovery has been overlooked by Mozart scholars, and her book—which summarizes the letter’s contents but omits the transcription and fails to give a precise archival reference—is long out of print.

Just how drafts composed by Firmian in Milan ended up in the court archive in Vienna remains unclear, although they might have been transferred at the time of the Napoleonic invasion, or perhaps in 1859 when Austria ceded control of Lombardy to the Kingdom of Italy. The fair copy of Firmian’s letter to Sporck (that is, the copy Firmian actually sent), which one might expect to be in the Viennese court archives, has yet to be found.

Firmian’s letter to Sporck is dated 9 Feb 1771, just five days after the Mozarts had departed Milan for Venice. Firmian writes that he has been informed by way of a letter from Maria Theresia’s secretary that the empress is leaving it to Firmian to choose the author and composer for the wedding serenata. (The reference may be to Carl Joseph von Pichler, the empress’s private secretary.) Firmian suggests that the libretto of the serenata might be assigned to Giovanni Ambrogio Migliavacca (c. 1718–c. 1795), who had written the libretto for Gluck’s Tetide, composed for the wedding of Archduke Joseph and Isabella of Parma in 1760. This is the only reference to Migliavacca in the correspondence about the wedding in 1771, and by the following month, Firmian had settled instead on Giuseppe Parini (see our entries for 9 Mar 1771 and 17 Oct 1771). Maria Theresia’s correspondence with Firmian regarding the serenata, if it survives, has not been found.

Regarding the choice of composer, Firmian writes:

Per la Musica crederei affatto proprio il giovane Maestro di Cappella Mozart di Salisburgo, già cognito alla Corte, il quale ha fatto qui la Musica per la prima Opera di questo Carnovale, che ha piaciuto moltissimo, e a segno, che resta già scritturato in concorso di uno de’ primi Maestri d’Italia, per le due Opere del 1773, per il qual’anno sarà probabilmente scritturato anche per il Teatro di Torino. Tale di lui Musica è stata esaminata dai migliori Maestri sì di questa Città, che forestieri, e tutti l’hanno sommamente lodata, il di lui merito è pur conosciuto dal Maestro Hasse, ed io sono persuaso che impiegherebbe tutto il suo talento per farsi onore in questa occasione.

For the music I would think completely suitable the young Maestro di Cappella Mozart of Salzburg, already known to the Court, who wrote the music here for the first opera of this carnival, which pleased very much, and who consequently has already been engaged along with one of the leading masters of Italy for the two operas of 1773, for which year he will probably also be engaged by the theater in Turin. His music has been examined by the best masters, both of this city and abroad, and all have praised him most highly. His merits are moreover recognized by Maestro Hasse, and I am convinced that he will employ all his talent to do himself honor on this occasion.

Mozart was already known to the court from his visits to Vienna in 1762 and 1767–68. Firmian’s “la prima Opera di questo Carnovale” (“the first opera of this carnival’) was Mitridate, first performed on 26 Dec 1770, which had completed its run on or around 17 Jan 1771, just three weeks before Firmian’s letter to Sporck (see our entry for 16 Jan 1771). The clause “che resta già scritturato in concorso di uno de’ primi Maestri d’Italia, per le due Opere del 1773” (“who consequently has already been engaged along with one of the leading masters of Italy for the two operas of 1773”) refers to Mozart’s commission to compose one of the two operas for Milan in the carnival season 1772–1773, the opera that became Lucio Silla. The contract for Lucio Silla, which survives, is dated 4 Mar 1771 (Dokumente, 119); Leopold Mozart first refers to this commission on 18 Mar in his letter quoted above. But Firmian’s letter to Sporck shows that the choice of Mozart was already settled nearly a month earlier.

The clause “per il qual’anno sarà probabilmente scritturato anche per il Teatro di Torino” (“for which year he will probably also be engaged by the theater in Turin”) refers to Firmian’s understanding that Mozart would likely also be commissioned to write an opera for Turin in 1773. Wolfgang and Leopold had just returned to Milan on 31 Jan 1771 from a two-week excursion to Turin, taking with them letters of recommendation from, among others, Firmian and Antonio Greppi, manager of the Teatro Regio Ducal in Milan (see our entries for 9 Jan 1771 and 26 Jan 1771). Although in the end, this commission did not come to pass, prospects for it seemed good in February 1771.

Firmian closes his case for Mozart by writing:

In paese non abbiamo altri Maestri di qualche grido, che il solo Sammartino Maestro di Cembalo della Ser.ma Sig.ra Principessa di Modena, ma quanto hanno incontrato le di lui composizioni di Chiesa, altrettanto, sull’esperienza fattasene più volte, non ebbero incontro quelle da lui fatte per altre occasioni. [...]

In this city we have no other masters of similar acclaim apart from Sammartini, Maestro di Cembalo to Her Serenity, the Princess of Modena; but although many of his church compositions have met with success, repeated experience of his compositions for other occasions has shown that they did not. [...]

The reference is to Giovanni Battista Sammartini (c. 1700–1775). Firmian argues, in effect, that apart from Sammartini’s church music, his other compositions (by implication his secular vocal and dramatic works) have generally not been successful, and that Mozart, whose Mitridate had just been a considerable success in Milan, will be a better choice.

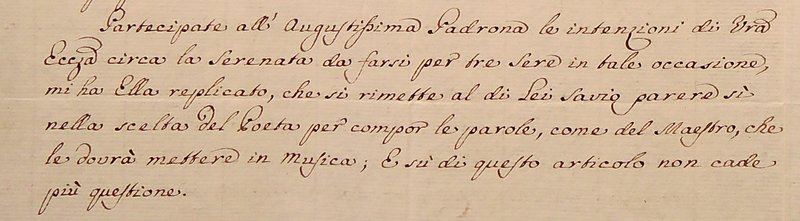

On 21 Feb 1771 Sporck wrote in reply:

Count Sporck to Count Firmian, 21 Feb 1771

(HHStA, Ält. ZA, Kart. 84, 6v)

Partecipate all’ Augustissima Padrona le intenzioni di V[ost]ra

Ecc[ellen]za circa la Serenata da farsi per tre sere in tale occasione,

mi ha Ella replicato, che si rimette al di Lei savio parere sì

nella scelta del Poeta per compor le parole, come del Maestro, che

le dovrà mettere in Musica; E sù di questo articolo non cade

più questione.

Your Excellency’s intentions regarding the serenata to be given

on three evenings on this occasion having been communicated to

our most August Patroness: She has replied to me that she defers

to your wise opinion, both in the choice of the poet to compose the

words, and the Maestro who will set them to music; and on this point,

there are no further questions.

In other words, Sporck has conveyed to Maria Theresia Firmian’s proposals from the letter of 9 Feb, and she has no objections to his choices regarding the serenata, trusting Firmian’s judgment in the matter.

Firmian’s use of the title “Maestro di cappella” to refer to Mozart (he also uses this formulation in his letter to Parini on 19 Aug 1771) could be simply a pro forma honorific. However, we should not rule out the possibility that Firmian already had in mind proposing Mozart as maestro di cappella for the new court that Archduke Ferdinand would soon be establishing in Milan, and Firmian may have been using the title to imply that Mozart was already qualified for that position (see the discussion in our entry for 17 Oct 1771).

Our site includes three further extracts from draft letters by Firmian regarding preparations for the wedding in Milan. On 7 Mar 1771, Firmian wrote to Count Lorenzo Salazar, direttore of the Regio Ducal Teatro, instructing him to send a letter about the commission for the serenata to Mozart. This is the letter that Wolfgang and Leopold received in Verona, which Leopold alludes to in his letter of 18 Mar. On 9 Mar 1771, Firmian wrote again to Sporck, telling him that Mozart had been informed of the commission, and that Firmian had chosen Parini to write the libretto. Finally, on 19 Aug 1771, just two months before the wedding, Firmian wrote to Parini from Vienna asking him to shorten the libretto a bit in order that the serenata not last longer than two hours.

On 26 Mar 1771, a letter from Firmian was read to the senate in Milan, informing them that Archduke Ferdinand would be arriving from Vienna in the autumn, and that preparations for receiving him should therefore begin (see the report in Notizie del Mondo, no. 27, Tue, 2 Apr 1771, 211–12).